How Santa Barbara Got Its Post Office

Excerpted from “California Editor” by Thomas M. Storke, past postmaster and longtime editor and publisher of the Santa Barbara News-Press.

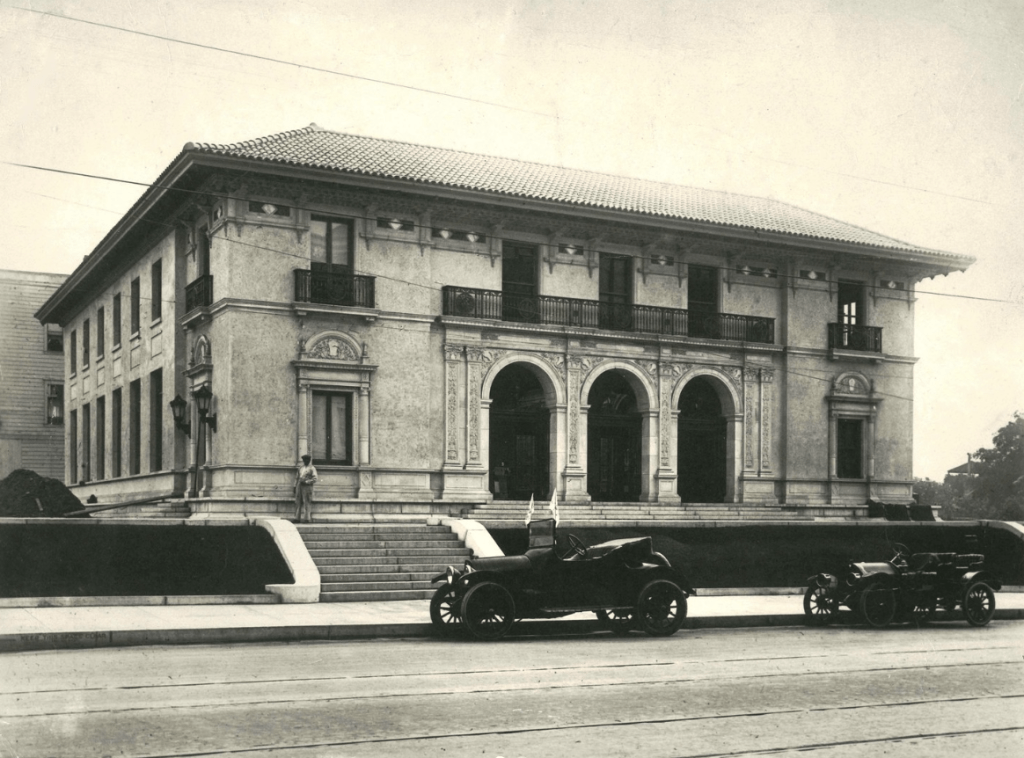

The Santa Barbara Post Office apparently had been built [in 1914 at State and Anapamu, with Storke as its first postmaster] without taking into account possible future growth in population and the needs of its postal service. During the two decades between 1914 and 1934, Santa Barbara had more than tripled in population. The volume of mail had quadrupled. To move the normal daily volume of business it became necessary to lease outside space, until the situation became untenable. Something had to be done about it, and very soon.

Washington was alerted to our problem. Word soon reached Richard Ambrose, our local postmaster, informing him that the federal architects planned an addition which would cost $175,000 and that no further sum would be forthcoming.

Ambrose was highly displeased with the plans. They did not conform to Santa Barbara’s established Spanish-American theme, but resembled a three-story shoe factory. He protested to Washington but was informed that no change would be considered.

The local chamber of commerce added its objections and was also turned down by Washington. As a last resort, I was asked if I would lend a hand. I left for Washington immediately, at my own expense, and sought out the Third Assistant Postmaster General who formerly had had charge of post office construction.

He informed me that he no longer had jurisdiction in this matter; that FDR had established a “Procurement Division” within the framework of the Treasury Department, headed by Rear Admiral C. Joy Peoples, who was the final arbiter in all such cases.

I was discussing Santa Barbara’s problem with this official when Admiral Peoples himself stepped into the office and we were introduced. He all but shut the door in my face on his way out, refusing even to discuss the matter. Apparently he was somewhat annoyed by the heavy volume of correspondence, which he had noted in the Santa Barbara Post Office file. At any rate, he said, it was too late now to be making changes.

A few minutes after the admiral’s rebuff I was in Postmaster General Jim Farley’s office pouring out my tale of woe. Jim said, “Tom, go see Admiral Peoples. He’ll take care of you, I’m sure.”

“But I just saw the admiral, Jim,” I protested. “I was lucky to escape by the door instead of a window.”

Jim had a hearty laugh. He replied, “I want you to see he admiral again. It’s too late today, so we’ll make it tomorrow.”

•

At 10 o’clock the next morning I was at the admiral’s desk. He had apparently been awaiting my arrival, for he was most gracious, and apologized for his curtness of the day before. He said “something had been bothering” him.

I spent the greater part of that day with Admiral Peoples. Our conversation had not proceeded very far before he rescinded the order for the non-conforming $175,000 post office annex. He authorized me to locate a suitable site for an entirely new post office building in Santa Barbara, on at least a 200-foot square lot. He also authorized me to negotiate for the purchase of this site, in cooperation with our district post office inspector Roscoe Knox of Los Angeles. The appropriation was increased from $175,000 to $485,000, and that did not include the $100,000 we spent for the land.

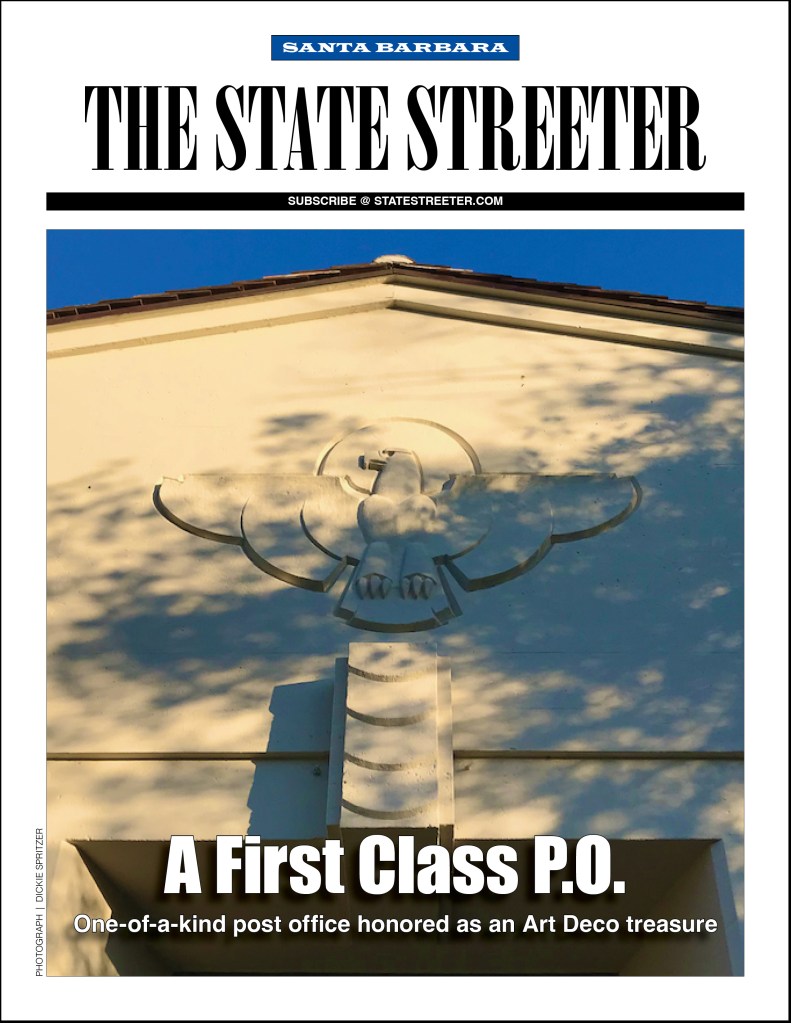

At the conclusion of these financial arrangements, the admiral and I had quite an argument over architectural design. He insisted that government architects would have to do the designing, adhering to long-established standardized specifications. I insisted that such a building might fit 99 out of 100 American cities, but would be out of place in Santa Barbara. The admiral finally called in his specialist on post office design. After a short debate, the admiral gave up. He recognized from my pleading of the case that none of his official architects could interpret the elusive sentimentality of Santa Barbara.

So, in the end, I was also authorized to select an architect. To get this all-important concession, I assured the admiral that if Santa Barbara could not find an architect willing to donate his services, we would guarantee payment of his fee out of our own pockets. There was no provision in the law to pay architects’ fees outside of those regularly employed by the federal government.

That same afternoon, before leaving for Santa Barbara, I telephoned one of California’s most celebrated architects, Reginald Johnson, at his home in Pasadena. He had designed the Santa Barbara Biltmore Hotel and other fine buildings and upper-class residences in our area. To my delight, as a personal favor to me, Johnson said he would contribute his extremely valuable services without cost. He requested only that we pay his draftsmen’s fees.

Before leaving Washington I told Admiral Peoples about Johnson’s altruistic gesture. It both pleased and astonished him. He later informed me that never before in history had a community been allowed to choose its own private architect to design a federally financed building.

•

The old Santa Barbara Post Office was to be used to house other federal agencies such as Social Security, Internal Revenue, etc. However, it was found that the cost of remodeling was more than the government felt justified in spending. When I heard about this, I requested Admiral Peoples to place a low figure on the property and offer it for sale to the county for use as a ready-made art gallery. Our community had long needed such a facility.

While this proposal was being studied, I aroused the interest of one of our foremost citizens, the late Buell Hammett, a patron of the arts and a nationally known collector. Hammett and I worked out a plan which was adopted by the county supervisors whereby Santa Barbara County would offer the government $50,000 for the old post office — a mere fraction of its actual value.

To our great joy Admiral Peoples accepted this offer, and Hammett organized the Santa Barbara Museum of Art December 7, 1939, as a nonprofit perpetual corporation under the laws of California.